🍞 The Money Games - Part 4

A 5-Part Guide to Earning, Saving, Borrowing, and Investing Money Wisely

Sup Loyal Bread Crumbers 👋🏻,

Here’s Money Games - Part 4. Hot off the presses!

Introduction

For all the newbies in YM2 town, go back and check out Money Games Part 1, 2, & 3.

That’s required reading material. You’re in the big leagues (of thinly read finance blogs).

With that said, let’s get started.

Running, Stupidity, and Investing

What’s the name for a person who trains for a marathon by running 100 meter sprints? That’s right, an idiot. We rarely see that level of stupidity in running. The same can’t be said for investing. Why? Because dumb investors don’t know the race they’re running. The smart investor knows the race she’s in and the variables that matter. For the runner, those variables are distance and time. For the investor, they’re quantity, time, and risk tolerance. Said another way, the smart investor asks herself, ”How much money do I need? When do I need it? And can I afford to lose it?”

This essay is designed to help us find answers to these questions. Let’s begin.

Quantity (How Much Money Do You Need?)

Investing involves buying an asset today with the expectation that it will be worth more in the future. This asset can provide future payments (known as dividends), a lump sum if you sell it, or a combination of both. Your profit, or return, is the difference between the price you paid and the cash you receive from dividends or a sale.

Assets can be physical (like a house) or financial (like stocks and bonds). Financial assets can be hard to visualize, so I find it helpful to think of them as money-making machines. You feed them money, wait, and they eventually produce more money than you put in. But sometimes they blow up and destroy all your money, lol.

When people talk about all the different types of financial assets, I imagine a giant factory full of different money-making machines. Nowadays, most of these machines have one job: making money for our retirement. Why? Because retirement isn't cheap. Just look at the math:

Let’s assume you’re a 25-year-old in 2024. You want to retire at 65 and you expect to kick the bucket at 83. That means after you retire, you’ll need to pay your living expenses for 18 years (at least) with no salary. If today, your annual cost of living is $80k, when you retire in 2064 (assuming 3% inflation) it will be $250k(ish). That’s assuming Social Security goes bankrupt.

If Social Security survives, the numbers are a little less scary. In 2064, the U.S. government will give you $150k(ish) annually in Social Security benefits.

In the best case, you’ll need about $100k per year for living expenses ($250k - $150k) in retirement. In the worst case, you’ll need about $250k per year.

This means you'll need between $1.8 million and $4.5 million to cover 18 years of expenses. If you save $10k per year for the next 40 years ($400k total), you’ll still be $1.4 million to $4.1 million short.

You need a money-making machine capable of multiplying your money by 11.25 times.

Time (When Do You Need the Money?)

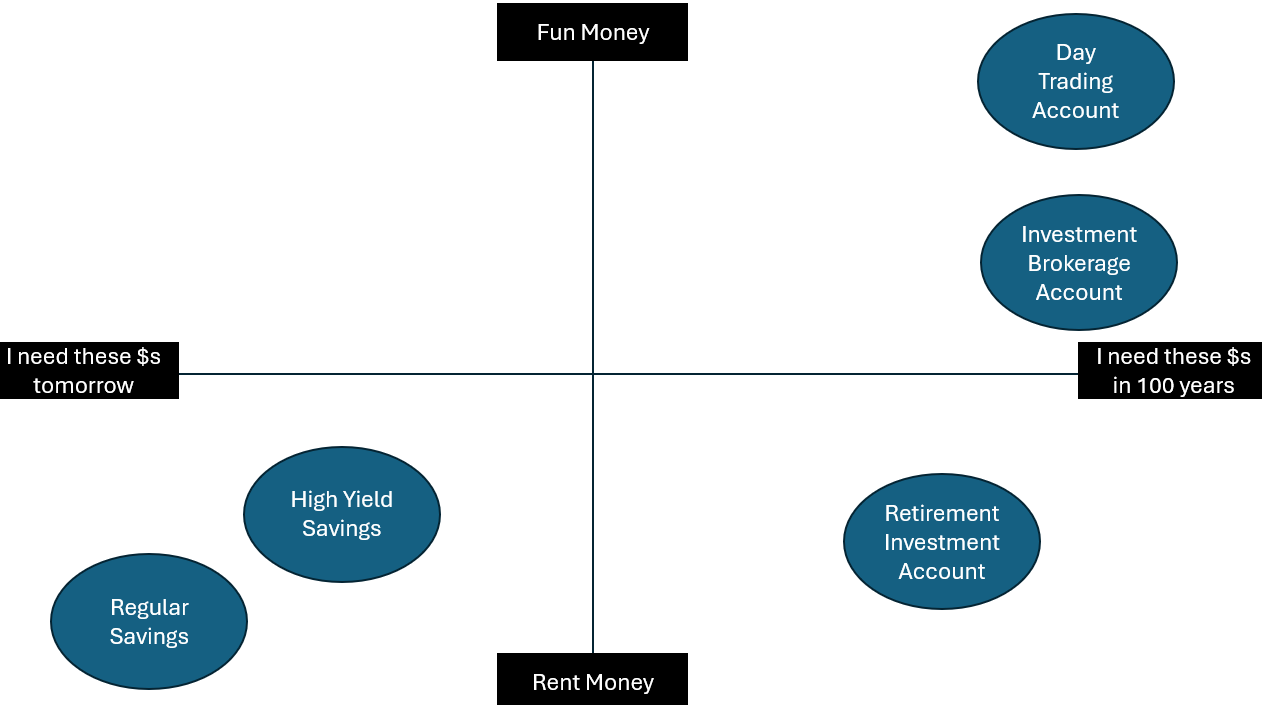

Now that we know how much money we need, the next question is when we need it. In our retirement example, we need it in 40 years. Timing is crucial because it helps us choose the right financial asset to buy.

Think of a factory full of money-making machines. These machines are grouped by how they multiply money and how long it takes them, or their "run time." For example, one row of machines can double your money in 10 years, while another can do it in 1 year.

Why is run time important? The shorter the run time, the riskier the machine. A machine that doubles your money in 1 year is much riskier than one that does it in 10 years. Fortunately, you have 40 years, so you can choose less risky machines.

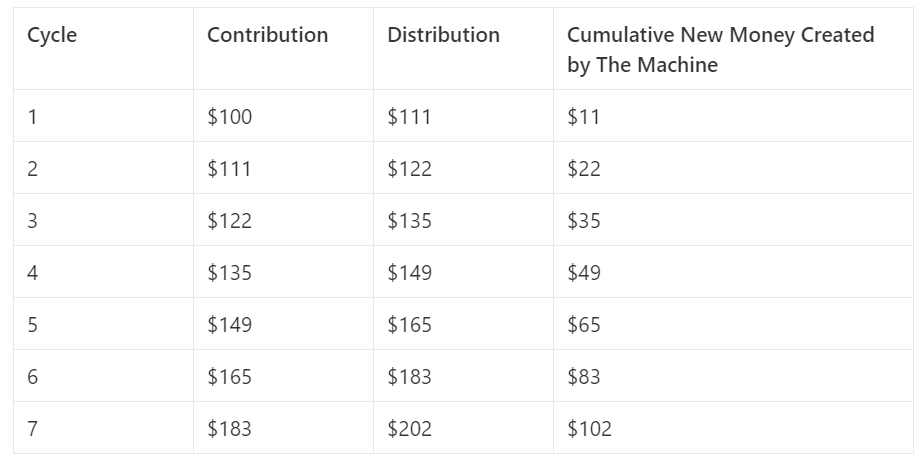

One of the most popular and trustworthy machines, the S&P 500, has delivered a 10.56% average annual return. It can take $100 and in 12 months (on average) it will spit out $110.56. (1.11x).

At first glance, the machine is unimpressive. But the machine only ran 1 cycle. If it ran another cycle, it would take that $110.56 it created and spit out $122.23. If it ran for 7 cycles, it would have doubled your initial $100.

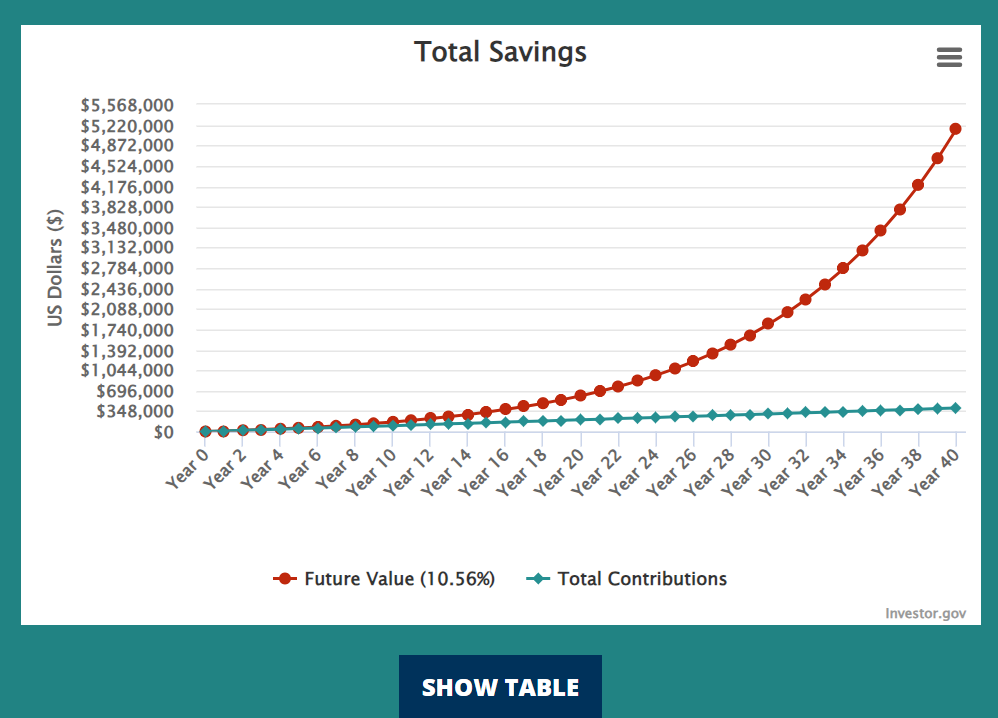

Could this machine 11.25x your money in 40 years? Let’s see. If we run it for 40 cycles and each cycle we put in $10k. At the end of 40 cycles, it will have taken $400k and created $5.2 million. That’s 13x your total investment! We call this money magic compound interest.

Sound too good to be true? Well, it is. Sort of. Read on.

Risk Tolerance (Can You Afford to Lose The Money?)

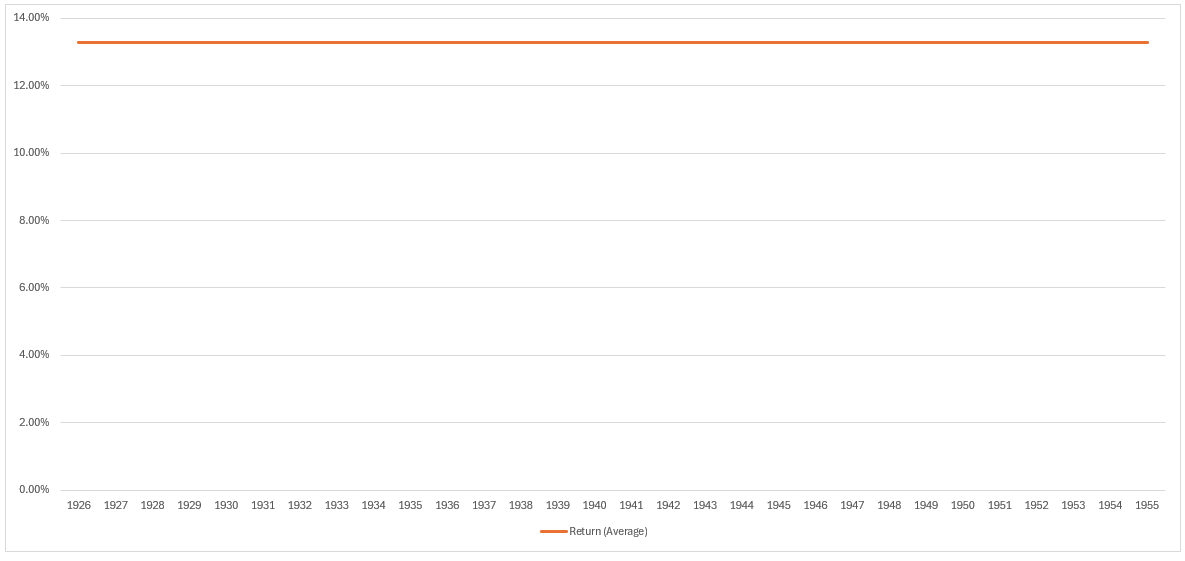

Did you notice the sleight of hand I used earlier? I mentioned the average annual return of the S&P 500 over the last 100 years is 10.56%. Averages can be misleading. If I tell you a basketball team’s average height is 6 feet, you might think each player is about 6 feet tall. But you'd be wrong. Most of the team is 5 feet tall. How? Three players are 5 feet, one is 7 feet, and one is 8 feet. Averages can distort reality.

The average annual returns of indices like the S&P 500 can be similarly misleading. In theory, a 13% average annual return feels something like this:

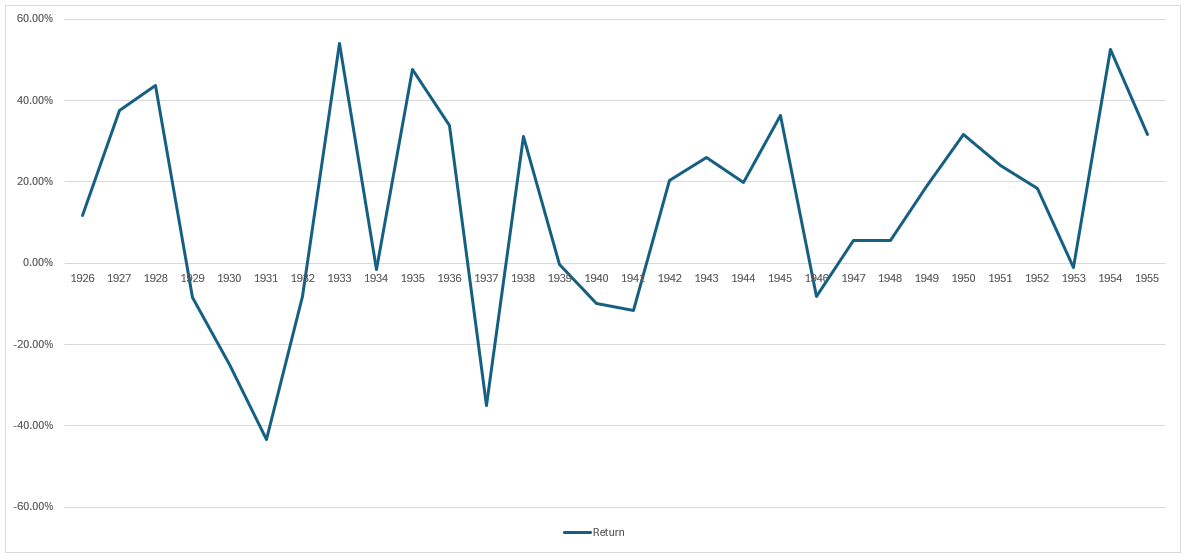

In reality, it’s a roller coaster:

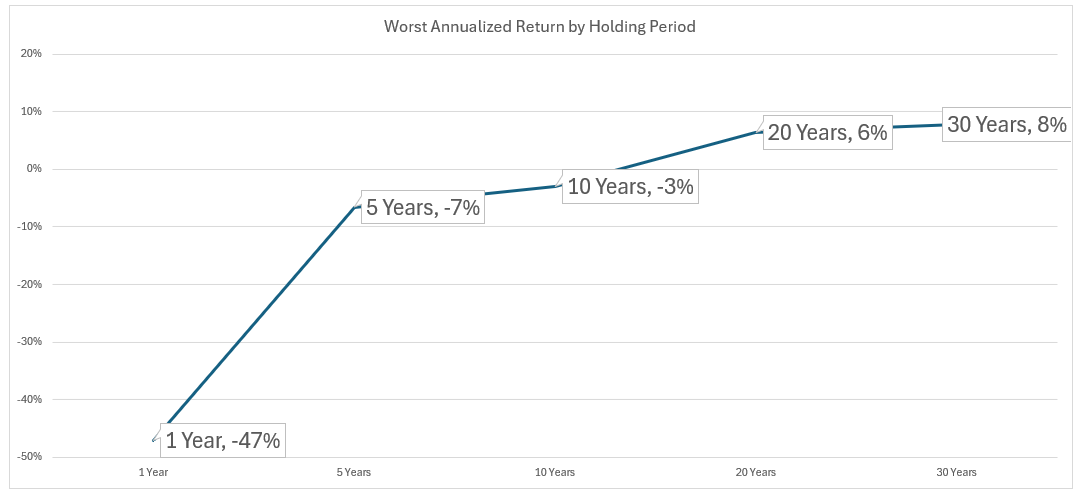

That unpredictable roller coaster is volatility. Financial assets are prone to this volatility. But don't lose hope. Over the long term, these fluctuations balance out. Looking at the S&P 500, you might have a terrible year or a bad five to ten years, but with a 20+ year investment horizon, you'll likely be okay.

A long-term investment is more resilient. When a big drop in value happens (which it will), you'll remember that, over time, losses are likely to be balanced out by gains.

But what if you need that money in 5 years to buy a car? In that case, you'd be tempted to sell if things went poorly because you can't wait for the big gain.

A short time horizon doesn't mean you can't invest. It just means you need a different kind of investment. The S&P 500 isn't suited for short-term investors or savers.

Types of Money-Making Machines

A High Yield Savings Account (HYSA) is a good option for a 5-year time horizon, offering a 1% to 5% annual return with minimal risk. By investing $10,000 in an HYSA today, you could have between $10,500 and $12,700 in 5 years.

How does this work? The bank earns interest for you by using your HYSA money to buy government debt, such as 1-Year U.S. Treasury Bills, which are considered risk-free. The U.S. government is unlikely to default on its debt, and if it does, we have bigger problems.

Quick Summary

Let’s pause and summarize what we’ve covered so far:

Like a smart runner, an intelligent investor knows the race she is running.

To find the perfect money making machine, we need to know (1) how much money we need, (2) when we need it, and (3) if we can afford to lose it.

A machine that promises to 2x your money in 1 year is much riskier than one promising to do it in 10 years.

The longer you let compound interest work for you, the more magical it becomes.

Average annual returns can be misleading. Year to year performance is volatile. Averages hide this fact. Long-term returns (20+ years) are more stable.

The money you need in the next 1 to 15 years should be put in a low-risk, low-return investment like a HYSA.

Now that you know how to choose the right investment, where can you find one?

The Retailer

If you need a snow blower, you might head to Home Depot, Lowe’s, or Costco. Different retailers often supply the same product. Investment management companies work the same way. You can buy the S&P 500 index fund at Vanguard, Charles Schwab, or Fidelity.

The most popular method for investing is through mutual funds. Before mutual funds, everyday consumers couldn’t afford large-scale investments. Buying one share of the 500 largest U.S. companies could cost over $100,000.

Mutual funds helped small investors pool their money. The mutual fund manager (e.g., Vanguard) raises money from thousands of small investors. This pooled money is called a fund. Each investor owns a percentage of the fund based on their contribution. It’s a mutually owned fund. Get it?

In an S&P 500 mutual fund, the manager uses the fund’s money to buy shares of the 500 largest U.S. companies. Each investor in the fund, due to its shared ownership structure, owns a piece of these companies.

Mutual funds became the "it product" in investing for another reason. Starting in the 1970s, the U.S. government began incentivizing citizens to buy mutual funds to finance their retirement. Why? Because Uncle Sam didn’t want to keep bailing out pension funds.

The Uncle Sam Special

How did Uncle Sam get people like you and me to start funding our retirements? One word: taxes. He used taxation incentives to sway public demand. Taxes and demand tend to be negatively correlated. Raise taxes on a product, and demand drops. Decrease taxes on a product, and demand soars.

Uncle Sam created special, “tax-free” retirement investing accounts. The term “tax-free” is a bit misleading. It’s better to think of these accounts as “tax-advantaged.” You pay fewer taxes on the profits made in these accounts than in a regular investing account. However, you don’t fully escape Uncle Sam’s reach. Let me explain.

A regular investing account is taxed twice. Uncle Sam gets you on the way in and the way out. On the way in, he taxes a chunk of your paycheck, called “income taxes.” But he’s not done. If you buy an investment from Vanguard and it turns $100 into $200, he wants part of that $100 profit. That $100 profit is known as capital gains, and Uncle Sam takes 15-20%.

In special retirement investing accounts, Uncle Sam only taxes you once, either on the way in or the way out. The way-in option is “post-tax.” The way-out option is “pre-tax.” The names refer to the type of money going into the account. Has Uncle Sam taken his cut? If so, that money is post-tax. If not, it’s pre-tax.

In a pre-tax plan, Sam allows you to put money into the account without paying income tax. In this scenario, he only taxes the capital gains that are created. In the post-tax version, you pay income taxes, but you keep all your capital gains.

The Uncle Sam Special for retirement investing is a no brainer. Fewer taxes = more money for you.

Types of Uncle Sam Specials

There are several names for pre-tax and post-tax retirement investment accounts, with the three most common being the 401(k), IRA, and Roth IRA.

A 401(k) (or 403(b) for non-profits) is a pre-tax, employer-sponsored retirement account. You tell your employer what percentage of your paycheck to put into the account. Your employer deposits that percentage of your pre-tax salary into the account before paying you. You can then use that money to invest in options like an S&P 500 mutual fund. Some employers even match 401(k) contributions. For example, if you contribute $1,000, they might add another $1,000, up to a certain percentage of your salary. This match is free money—take advantage of it.

If you are self-employed, you can use an Individual Retirement Account (IRA). It’s like the 401(k) but without the employer match. The Roth IRA is the post-tax version of the IRA. If you’ve got money left over after hitting your employer match, open a Roth IRA. You can contribute up to $6,500 per year to this account in addition to your 401(k).

Still have money left over after hitting your employer’s 401(k) match and maxing out your Roth IRA? Go back and max out your 401(k). You can contribute up to $22,500 per year to your 401(k). That $22,500 does not include your employer match. So, in reality, you can contribute $22,500 on top of what your employer puts in.

Still have leftover cash? Donate to charity, you rich, heartless buffoon!

Dark Side of Money-Making Machines

I've described money-making machines as magical entities that run on their own. That’s not true. There is a labor component. Some sad SOB is cranking the machine. If it is an equity machine (like owning the S&P 500), the employees of the company are cranking the machine on your behalf. The profits they create are owed to you, the owner.

Imagine you work at Chipotle as a line cook. Unless you own Chipotle stock, your labor is making someone else rich. Each dollar of profit you help generate goes into someone else's pocket.

If we are talking about a debt machine, the borrower does the cranking. The bank might be lending the money in your savings account to your neighbor (via a mortgage loan) so he can buy his house. He pays the bank interest and you see a small portion of that.

Ideally, we should avoid cranking other people’s machines. If we can’t avoid that, we should strive to be a laborer and an owner. That way, the profits we create go back into our pockets.

The most dangerous situation is being at the mercy of a lending machine with a high interest rate. Those are like a Chinese sweatshop. A credit card is one example. By failing to pay off the balance, we are forced to pay 30%+ interest rates. Simply avoiding credit card debt is a good investment. Think about it. By not paying someone else 30% interest per year, you avoid a huge opportunity cost. If you’re stuck in credit card debt, paying it off is a wonderful use of your money.

Other forms of lending are less sinister. As a rule of thumb, any loan with an interest rate higher than 8% should be paid off immediately (or just avoided from the start). The sooner you stop working for someone else’s money, the quicker you can build wealth.

The End

Phew. We’ve covered a lot of ground here, but I think the takeaways are pretty simple.

Know Your Race: Understand how much money you need, when you need it, and if you can afford to lose it. Then you'll know what to do with it.

Think Long Term: The longer you let your money earn compound interest, the wealthier you'll become.

Don't Be a Sucker: Investment returns are rocky in the short term. Stay smart and prepare for the bumps.

Exploit Uncle Sam: Make the most of tax advantages for your retirement investments.

Avoid Sweatshops: Don't work for someone else's money. Stay out of credit card debt, and if you're in, get out.

Bonus Points

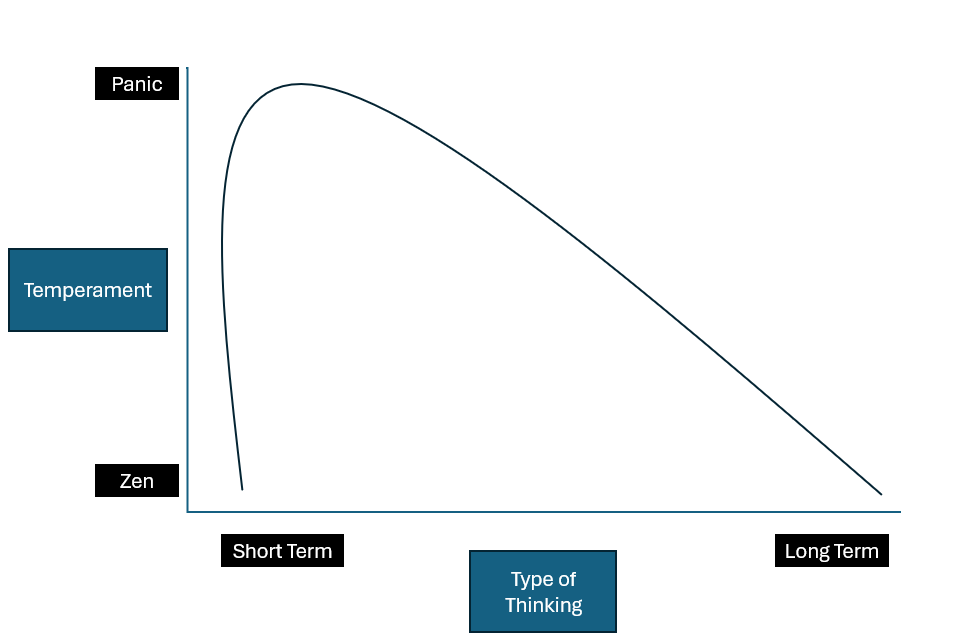

I tried to create a few graphics to explain my thinking. They’re not great but I tried.